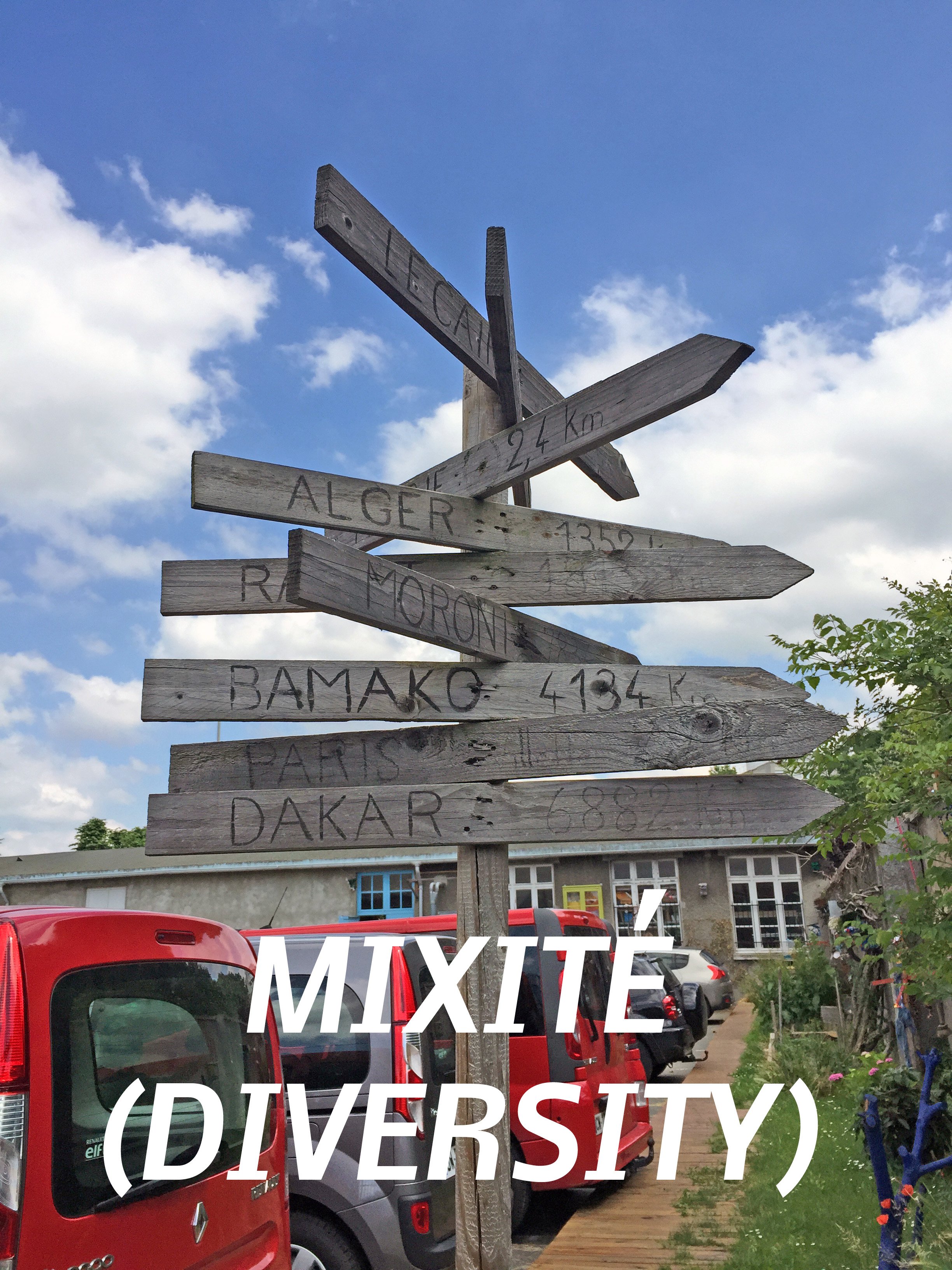

Season 2 Episode 2 - MIXITÉ (DIVERSITY)

Does a good social mix create greater security for urban residents?

This episode we're talking mixité or diversity. How does it affect public space socially and politically in the Parisian region.

Script

Jess 0:01

This is Here There Be Dragons. I'm your host Jess Myers.

[MUSIC]

Last episode we left off with Jean-Claude wondering about the benefits of mixité, or diversity, as we call it in English. Does a good social mix create greater security for urban residents? Before we dive into it, I'd like to talk about the words we'll be using on this podcast. I've decided to use some French words without translating them, because they can't be translated without losing some of their original meaning.

One of them is mixité. And when the French say it, *ding* "mixité," it means something slightly different than what we English speakers mean when we talk about diversity. In the US, the first thing we think about when we think about diversity is race. In France, mixité is primarily a question of class. Of course, race and religion are included in mixité, but they're harder to quantify since the French government is forbidden from keeping official statistics about race and religion.

Which brings us to another word that you'll hear a lot: populaire, *ding* populaire. In French, it doesn't mean being well liked. It refers to France's working-class groups, from factory workers to street sweepers. The French working class has a strong political history. They've built barricades and led revolutions, as you might know from Victor Hugo's Les Miserables.

[MUSIC]

A romanticized representation to be sure, but you get the idea.

As we talked about last episode, and if you haven't already, I recommend you listen to that first. Over a century ago, immigrants to France joined the populaire class, which added a history of race and religion to the word. Whether they work in factories, shops, or the street, the populaire class has created their own culture, entertainment, and language.

[SOUND CLIP]

They've been strong advocates for their rights, as well as crucial parts of the socialist and communist parties. Many of the French populaire class live in the banlieue, *ding* "banlieue", another French word we'll be using. The banlieue are suburbs, but unlike American suburbs, many of them are former factory towns with high concentrations of social housing projects.

So this season, we'll be using words like mixité, populaire and banlieue to hold their historical meanings in French and we'll keep refining their meanings throughout this podcast. If you're ever confused about a word we use on the show, check the glossary that we have on our website, HTBDpodcast.com.

So mixité: does it keep us safe? Although France is thought to be fairly homogenous, Paris is anything but. Paris and its surrounding boundaries have been a magnet Metropolis for different waves of migration.

If war is a catalyst for migration, so is colonialism. In the 20th century, France had large colonies across the globe and experienced several land wars.

JACQUELINE 3:00

“Alors je suis Jacqueline Houdart, je suis née à Paris, le 12 juillet 1922”

Jess 3:07

We went to visit Jacqueline at her house in Bois le Roi, a South Eastern banlieue tucked into a bend of the river Seine.

JACQUELINE 3:16

long enough.

Jess 3:19

She invited us to sit with her in her garden and told us how as a young girl, before the beginning of World War Two, she remembered a peaceful mix of French natives and European immigrants.

JACQUELINE 3:31

“alors il est certain que y avait des quartiers populaires dans Paris…”

[Translation]

There were populaire neighborhoods in Paris, there were areas that were very marked by certain populations. There were Polish, there were many Italians. It was very diverse. Everyone got along well. I was in primary school. I remember there was a little Polish girl. There were two Italians. There weren't all these conflicts, like we have now between nationalities.

FRANCK 3:56

“maintenant pour avoir des conflits de nationalités…”

Jess 3:59

Not all older generations are so at ease with this mix. Franck comes from a small town in the West of France, in a region known for its strong Catholic identity. When he moved to Paris, Franck's parents had some reservations.

FRANCK 4:12

“Mixité est est quelque chose qui leurs fait peur…”

[Translation]

Mixité is something that scares them. I come from a small town that was very homogeneous. It was a very Catholic town, kind of the Breton version of the "Little House on the Prairie." When we got to a big city and saw veiled women, it was stressful for my parents. I spent some time in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, Chinatown. So my parents came to visit me. Seeing so many Chinese shops with lots of Chinese lettering...it was more than curiosity. It was concern.

“...curiosité, c’était de de d’inquiétude.”

Jess 4:44

The obvious difference between the immigrants Jacqueline remembers and the ones Franck's parents are so concerned about is race. Although it was difficult for other Europeans to integrate into French society, especially Jewish refugees, for them, cultural integration was easier to achieve. Immigrants from the colonies and non Western nations were not so lucky. Aurélie is a French lawyer in her 30s. 15 years ago she moved to Paris from her native Reunion Island, one of France's departments off the coast of Madagascar. She remembers when she was harassed on a bus after she moved to a Western banlieue.

AURÉLIE 5:19

“Et Levallois-Perret j’ai pas du tout aimé…”

[Translation]

I didn't like Levallois-Perret. It's pretty dead and it's very racist. I was on a bus and I was verbally abused by a lady because I just answered the phone and I spoke softly too. She said, "where you're from, you can pick up the phone like that, but not here." I didn't say anything. I left the bus. I was shocked because I've rarely experienced instances of racism. I wasn't doing anything wrong. So I got off and said, "well okay, no to that neighborhood." I'm not Parisian. When you look at my face, I could pass for foreign. I could pass for a French person with an immigrant background.

Jess 5:55

To her, mixité is a source of safety for minority groups because people become exposed to other cultures and identities.

AURÉLIE 6:02

“Bah parce que moi-même je viens d’un milieu multiculturel…”

[Translation]

I feel safer in a cultural mix. I come from a multicultural environment. On Réunion Island, it's like that. In Ménilmontant, I feel comfortable because while it's pretty mixed, there's people like me who are from different cultural backgrounds, instead of being insulted in the street because I answered the phone. Honestly, it's no contest.

“...pas photo oui.”

Jess 6:28

Jacob, who moved to France from the US 15 years ago, had very similar feelings of looking for belonging. He encouraged his husband to move away from his family's aristocratic neighborhood in the 17th arrondissement.

JACOB 6:41

I helped him to move away from the, what I call the, bourgeois part of the 17th because that's where his family was, to this more popular area, more diverse area, bigger gay community. Yeah, more open and I just felt like it was a more comfortable place for us to settle and just attractive to me to be in an area that's more diverse. You fit in better with people that are from different backgrounds and cultures. It was more appealing than the very conservative, very wealthy, old wealth aristocratic part of the 17th.

Jess 7:13

When talking to Parisian residents, two neighborhoods came up again and again as examples of mixité done right. Belleville and Ménilmontant are neighborhoods in the 19th and 20th arrondissement of Paris. Both of these neighborhoods are historical landmarks for the popular class. In the second half of the 19th century, Belleville and Ménilmontant were untouched by Baron Haussmann's massive reconstruction of Paris. This means that instead of the enormous boulevards you see in the center city, Belleville and Ménilmontant maintained their small winding streets, cramped workers housing and cheap cafes. When it comes to mixité, these neighborhoods seem ideal, where different social and cultural groups can peacefully coexist. Léopold, the 30-year-old editor of the Funambulist magazine, sees Belleville as an important intersection of history, while Steffi sees the mix of Ménilmontant as a crucial part of its liveliness.

LÉOPOLD 8:07

Carrefour of Belleville is a perfect example of that because on the one hand, you have historically a sort of white working class, that was complemented by more North African or West African working class, to which was added also a Chinese community, a Jewish community. It still marks a limit between the part of the East of Paris that is under relatively fast pace of gentrification at this very moment. You do have those sort of social and racial mixités that all collide at this one point, which I think is quite interesting in the heterogeneity that it creates.

STEFFI 8:49

“Ménilmontant et en fait… en fait je sais pas si”

[Translation]

Before, there was a really big Muslim cultural community. People aren't all Muslims, but basically you had a lot of young people, quite a few Lebanese too. And when I went home at night, I felt really safe, because there was so much life. People talked to each other, there was a community. You had plenty of other people, Europeans, Asians, because Belleville is not far away. Lots of different people. There was a real life in the Ménilmontant neighborhood.

JENNIFER 9:25

“Et là Belleville, après oui y…”

[Translation]

Belleville definitely has its problems. But when you go there, you really get the emotion that this mix is still intact. During Ramadan at night, you see people peacefully ending their fast in the square, putting out large tables. It's a really beautiful sight to see that there's this very strong mix with the old generation that's been there for years and years. There's also a big Asian, especially Chinese, community. Next to it, there may be a new bar, but both want to work together. I grew up in the banlieue. I still want to see people of all origins in the streets. It's not idealistic to say that. It's just part of my life. It's part of what I know. It was where my friends come from, where I grew up, people came from everywhere. So I want to see that. But also at the same time, I want to have my drink in a cool place, where I feel like I'm in Berlin or Brooklyn, because that's also my life. And so I want to be able to have both parts of my life in the same place.

“...Is the power just don't do the accessories to set the button measure,”

Jess 10:26

Jennifer, a 26 year old journalist, echoes Aurélie's words, it's the unknown that makes us feel unsafe. And that's why, to her, mixité is a good thing.

JENNIFER 10:37

“Parce qu’on est avec ce qu’on connaît…”

[Translation]

We're comfortable with what we know, and a mix of everyone gives us a sense of well-being. Suddenly, there isn't this fear of the unknown, because I think that the feeling of insecurity has a lot to do with the unknown. We don't know this neighborhood, so we fear it. We were told that there were drug dealers, so we fear it. Oh, they're a little too black or a little too Arab, so we fear it. It's because people are afraid of what they don't know. So being in a place where you have a little bit of everything, people from immigrant communities, young, active people who can sometimes struggle like us, people who are starting a family. All three are my life, so I feel good. I feel at ease. I feel safe.

“...donc je me sens à l’aise, donc je me sens en sécurité.”

Jess 11:23

Mixité can seem like a utopian dream. And it certainly isn't as simple as getting people to live next to one another. Politically, the concept of mixité is relatively new. It was first written into French law in the early 90s and has been at the heart of urban policies for the last 30 years. Mayors and local governments have made it a goal to achieve mixité from the top down. Samia, a 60 year old journalist, is skeptical of who mixité is supposed to benefit.

SAMIA 11:53

“Mixité…”

[Translation]

Mixité is interesting because it adds value or elevates popular areas, and enhances them, but for those on top rather those on the bottom.

Jess 12:03

My producer Adélie spoke with Sylvie Tissot, a political science professor and sociologist at the University of Paris 8, in Saint-Denis. Like Samia, Professor Tissot believes that mixité should be approached with nuance.

PROFESSOR TISSOT 12:17

“Là on a quand même un tournant qui est symptomatique aussi d'un passage…”

Jess 12:20

She says it was a turning point symptomatic of changing from a rhetoric that focuses on the reduction and dissolution of social inequalities to one that simply manages social inequality and better disperses it in space. She believes that mixité changes the political narrative around poverty. Instead of attacking inequality and considering policies that eliminate poverty, politicians are saying that poor people shouldn't be too concentrated, shouldn't be too visible in urban space. But Eric, a 38 year old musician, remembers the 80s and 90s when he was a teenager from the Eastern banlieue of Pantin, interested in hip hop and dance. Back then, he says, there were spaces that made it possible to cross these boundaries and created unexpected opportunities that he says no longer exist today.

ERIC 13:09

“Donc y a jamais eu de problèmes. Après, ce sentiment d’appartenance…”

[Translation]

There were never any problems. We were still teenagers, 15, 16 years old. We were lucky that we grew up in an underprivileged environment, you could say. It gave us legitimacy in hip hop culture. At the same time, we had access to very hip spots, could rub shoulders with models and artists from all over the world. We saw De Niro, Mondino, the top models of the 90s in this place called Bains Douches. We were lucky to have quote unquote dual membership. It is very rare. It's over now. Today, you're either well connected or you're from the ghetto, that's it.

Jess 13:41

Eric's experience was a form of mixité that he was able to seek out and achieve. When Maurice Blanc, a professor of sociology at the University of Strasbourg, spoke to my producer Adélie, he pointed out the struggle that arises when top down visions of mixité are enforced, especially when the broader needs of the lower class are not taken into account.

PROFESSOR BLANC 14:03

“est-que cette une mixité voulue ou est-que cette une mixité imposée…”

Jess 14:08

He asks, is it desired mixité or enforced mixité? This is already a classic issue for sociologists going back to the 70s. But urbanists, elected officials, and social housing managers won't hear it. Spatial proximity and social distance is still the reality today. Mixité as an urban policy is more of a government guided initiative. However, it can be dangerous to assume that the presence of wealthier residents will improve the lives of low income ones. Professor Tissot, who you heard from earlier, points out that there's no solid legal definition of mixité, but she argues that that might be for the best.

PROFESSOR TISSOT 14:49

“je ne souhaite pas forcément que l'action publique se donne comme objectif d'organiser le peuplement...”

Jess 14:53

She says she doesn't want public intervention to make organizing citizens its main goal. She thinks that's dangerous and that instead, public intervention should prioritize guaranteeing rights and equal treatment, especially as it pertains to housing. Both Jean Claude and Saïda work on the subject of social housing. In their work, they both see firsthand how complicated it can be to create mixité today through public intervention.

JEAN CLAUDE 15:20

“En fait, la loi…”

[Translation]

It says there must be 25% social housing in Paris. The law does not require that they be distributed in the arrondissement. That's the mayor of Paris, she decided to better distribute them. Municipalities in the Paris region who don't want to build the social housing, they're supposed to say, "we want to preserve the quality of life of our residents." In the minds of the people who don't want social housing next to their homes, there's this idea of insecurity, not from terrorism, but from the immigrant population in general.

This is partly a behavior that can be equated to racism, because that exists in the minds of many people, the association of social housing with the immigrant population. And when Paris Habitat had social housing projects in the 16th arrondissement, many local residents reacted by saying "it's bad for them, it's going to lower the value of their apartments, it'll bring a different demographic." I think it's very important to better distribute social housing in the city.

“...Et moi je pense par ailleurs que c’est très important de mieux diffuser les logements sociaux dans l’espace.”

Jess 16:22

The housing policy that Jean Claude refers to is called the SRU, “Solidarité et Renouvellement Urbain” – Solidarity and Urban Renewal. It's been in effect for almost 17 years. The current city government has been working to create more social housing in wealthy areas like the 17th arrondissement. A report published by the city council in September 2015, says the 19th, the area around Belleville, is almost 40% social housing, while the 16th is less than 4%. Here's Saïda.

SAÏDA 16:55

“Et après…”

[Translation]

Today, we try to create social housing where we're not expected to create social housing, like in the 16th arrondissement. In neighborhoods where we still have a high rate of homeowners, we're starting to promote social mixité and create social housing because there's a real need in Paris. We've gotten a foothold in those neighborhoods. It's not always easy. Not very long ago in the 16th arrondissement, the municipality wanted to set up a center for the homeless. The residents of the 16th were outraged because they were afraid that it will lead to insecurity.

Jess 17:35

Since this interview took place, the homeless shelter that Saïda refers to has survived two arson attempts. Although no one was injured, almost 50 people, including 24 children, were living in that shelter at the time. Months before its opening in October, 40,000 residents from the 16th arrondissement signed a petition against the shelter. Back to Saïda.

SAÏDA 17:58

“Moi aujourd’hui j’ai du logement social…”

[Translation]

Today, they have social housing in very beautiful neighborhoods, in the eighth, in the ninth. You do it little by little. At first, it's difficult. And then gradually, people get used to mingling and living together. There are inevitably prejudices on both sides. People are prejudiced, because they say to themselves, oo la la, what will it be like? And are they going to respect the streets? There will be trouble. Terrible things will happen if you put social housing here.

And on the other side, we people in social housing will say, oo la la will we suffer? How will we be received? Are they going to accommodate us? We often remind our tenants that they have a chance to live in a beautiful building, in a beautiful neighborhood, and they should participate in the preservation of the environment they're in.

And after that, what happens next, school, shopping, people meeting, the things people do around the neighborhood that will at some point abolish prejudice. But it can be a bit complicated. I had people who were in the eighth arrondissement and wanted to move back to the 18th. It happens very rarely to be honest. Most of the time, people still prefer to stay in the eighth. But it happens, that a family says the local shops are too expensive, or children are not very welcome in school, people give us side-long glances, I prefer to return to a populous neighborhood, where at least I have my bearings.

“...où au moins j’avais mes marques”

Jess 19:36

Protecting yourself by living in a neighborhood that fully reflects your identity, or you don't have to explain yourself or your culture, is a seductive proposal. It can push people to actively seek living arrangements where there is no mixité. In English we might call this segregation. But since France has a very different set of cultural politics, the reasons for social stratification in the city are very different as well. In French, the separation is called communotarisme. Who gets accused of withdrawing into these kinds of social bubbles is complicated.

Jess 20:10

Join us next episode when we discuss who gets to have a community and who doesn't. Are these choices dangerous for social cohesion or sometimes the safest choice possible? Is it really worth it to live in mixité?

Thanks for listening. This has been Here There Be Dragons, I’m your host Jess Myers. I’d like to say a special thank you to my sponsors at MIT Council for the Arts who made this season possible. Thank you also to Cory Lee Jacobs for the music in this season, check out his trio Octopus 2000 on bandcamp. I’d also like to introduce you to a new member of the team, co-producer Adélie Pojzman-Pontay. You’ll be hearing from her in the episodes to come. Be sure to subscribe and rate us on iTunes, Soundcloud, and Stitcher. If you want to leave us a comment email us at htbdpodcast@gmail.com or follow us on twitter at @dragons_podcast. And lastly, if you joined us last season you’ll know that every interviewee draws their personal maps of safety and danger, check those out on our brand new website htbdpodcast.com where you’ll find a number of treats including a glossary of French terms you may be curious about. Join us every other week for more stories of fear, identity, and urban life.